Your ADHD Brain Uses “Chaos” to Help You Focus

ADHD in 5-Minutes: From Frustration to Understanding [#006]

Skipping to this issue’s guide? Look for the header: "Building ‘Stim Menus’”

You know you're supposed to be working on that boring report.

Instead, you're reorganizing your phone's photo library, listening to a podcast about making smoked gouda cheese, and "writing" two emails in your head…that needed responses by yesterday morning.

Meanwhile, your coworker across the hall looks like they're starring in a productivity ad: they look calm, focused, and are quietly typing away on their laptop (on what appears to be a full-screen document).

Meanwhile, you're deciding which dog photo is going to be your new phone background, toggling between a dozen tabs trying to find which one is playing the podcast, and glancing at an email draft open on your 2nd screen you've been working on for almost 30 minutes (and, finally! you got the subject line nailed down).

Suddenly, you become uncomfortably aware of a sinking feeling in your gut, then a thought crosses your mind: "Seriously, why can’t I just focus?!"

For ADHDers, these situations are a bit too familiar.

But before we explore why this is so familiar, let’s set the stage by revisiting a summary from the first issue of ADHDn5.

Quick Recap: ADHD Summed Up

Fundamentally, ADHD can be summed up by one descriptor: inconsistency.

One week you’re crushing tasks; the next, you’re couch-locked. One day you’re productive; the next, everything feels impossible. One minute you’re focused; the next, you’re down a smoke-gouda-cheese shaped hole.

In this first issue, we homed-in on why this descriptor encapsulates an ADHDer's experience. In the two issues following that, I make the case as to why it really matters you learn to accept this.

Living with ADHD means you will have a consistent experience of being inconsistent.

If you don’t know, understand or accept this, then you will very likely take all of your inconsistent behavior, effort and performance, and use it as evidence for some kind of belief:

“I’m lazy…”

“I’m disruptive…”

“I’m unreliable…”

“I’m stupid…”

“I’m a burden…”

I don’t doubt these beliefs, and any like them, feel true or real.

However, if you can, I want you to suspend those beliefs just for a short while.

Let’s assume that inconsistency, wherever you notice it in your day-to-day life, isn’t about some flawed moral character so much as it is about major differences in how your brain perceives the world.

By the end of this issue, you'll recognize and maybe even appreciate how your ADHD brain is actually using (and causing) "chaos" in order to keep you focused…

A Brain That Craves (and Creates) the Storm

There are two distinct aspects of ADHD we need to bring into focus to grasp why this is:

Diminished Interoceptive Awareness

Higher Reward-Salience Threshold

This means we operate with a brain that is:

less able to detect our body’s current state, signals, and what it needs in a given moment, and

less able to notice signs of progress, paired with a higher standard for what feels rewarding.

While neurotypical brains can feel and respond to mild “rewards” from everyday activities—like the small satisfaction of checking off a to-do item or making steady progress on a project—your ADHD brain operates with what's essentially a glitchy progress-detection system.

Our brains differ in just the right way to make it harder to notice if we’re heading in the “right” direction, especially when doing any activities that lack sufficient stimulation.

For ADHDers, any sense of accomplishment or progress is difficult to register, particularly for any task that is low-stimulation, even if its “important."

Because, for ADHDers, low levels of stimulation equals a lower chance of noticing progress.

Consider this instead: If you were playing a game that didn’t provide indicators as to whether you were making progress on your objectives, you would very likely stop playing it. Why?

Because signs of progress and staying motivated are intrinsically linked.

This is so crucial to understand.

Unless sufficiently stimulated, the ADHD brain is unable to focus or remain motivated.

The Brain’s Crucial Questions

All brains, practically all of the time, are asking themselves two crucial questions:

(1) what do we need, and

(2) are we heading in the right direction?

Unfortunately, the ADHD brain struggles to see what it needs, and is regularly unclear whether progress is being made, so it defaults to either one or both of these options:

A) Wait, or

B) Stimulate.

If it doesn’t Wait, then it creates intense urges to seek stimulation, with the intent to increase its chances of seeing what it needs and if it’s heading in the right direction.

At some point, the ADHD brain distills its experience down to this:

higher levels of stimulation = increased chance of progress.

Below a certain threshold of stimulation?

Tasks feel pointless or “boring,” progress signals are too faint to detect, and your brain consistently scans for more stimulating alternatives.

Above a certain threshold of stimulation?

Tasks feel more interesting and relevant, signs of progress become more apparent, and true distractions are easier to filter out.

ADHD brains need more stimulation to answer the two crucial questions about needs and direction.

Unfortunately, and most of the time, it overcompensates in finding more stimulation…

The Paradox of Seeking Stimulation and Being Overwhelmed by It

ADHD can feel like living with countless paradoxes much of the time:

Struggling to focus on routine or important tasks yet hyperfocused on other activities

Feeling mentally exhausted while physically restless

Impulsive in some situations while overthinking or procrastinating in others

Needing stimulation to concentrate but quickly feeling overwhelmed by too much input

Most of these examples stem from the brain’s search for an optimal level of stimulation, which is a narrow zone rather than a single threshold.

In the attempt to find that zone, the ADHD brain overcompensates by seeking too much stimulation leading to a state of overwhelm.

When overwhelmed, the brain sends a compelling urge to Wait until it can make sense of all the stimulation.

Slowly, you dip down into that more optimal zone again, only for a few moments or minutes to pass when you feel an urge to Stimulate.

So you find something novel, interesting or “loud” to push you back up into that optimal zone.

Not long after that, you feel overstimulated and Wait…again…

Eventually this cycle hardens into a habit as we associate stimulation with progress.

Here's how it becomes a habit:

Important yet boring activity fails to reach your stimulation threshold

Your brain seeks more stimulation through novelty or urgency to increase its chance of noticing what it needs or if it’s making progress

Eventually, an optimal zone of stimulation is stumbled upon, and progress is made

Reward networks activate, telling us we’re heading in the right direction

We distill our experience into: "stimulation = progress"

This makes us more likely to seek stimulating activities (even if they’re not relevant)

Once the habit is formed, it can be challenging to break without deliberate effort and support…

…so, what can we do about this?

Breaking the Habit Through Deliberate Stimulation

Well, first, you need to figure out what mildly stimulating sources can be safely integrated into (or removed from) a given task until that optimal zone is more stable.

These sources are any item, tool, setting or activity that your sensory organs can detect.

For example: If I’m writing therapy progress notes and submitting them for billing, I need a visual timer above my monitor set for 20 minutes, with a mix of ‘Lord of the Rings’ LoFi music playing in my earbuds, with the document open on my 2nd monitor that is dimly lit, while sitting on a chair with a firm cushion.

This task, which I absolutely HATE, can take me anywhere from 60-75 minutes each day to struggle through.

But now I can complete it in 20-30 minutes with these four sources added in.

From 6-7 hours each week on notes…down to 2-3 hours…

Almost 60% less time is spent in a chaotic, resentment-filled state.

I still never want to do my notes, but this has made it wayyy easier.

Thankfully I have a simple way to create these stim menus for other tasks as well.

Interested in trying it out?

Building “Stim Menus”

This has taken me painful hours to distill, and while it doesn’t look like much, this is the exact step-by-step method I use to create reliable menus, even for my most loathsome tasks:

Step 1: Select Your Task

🔲 Pick one specific boring or overwhelming task you need to complete regularly. Select something you do that is routine (e.g. emails, reports, or household chores) or difficult to start.

Step 2: Testing Individual Sources

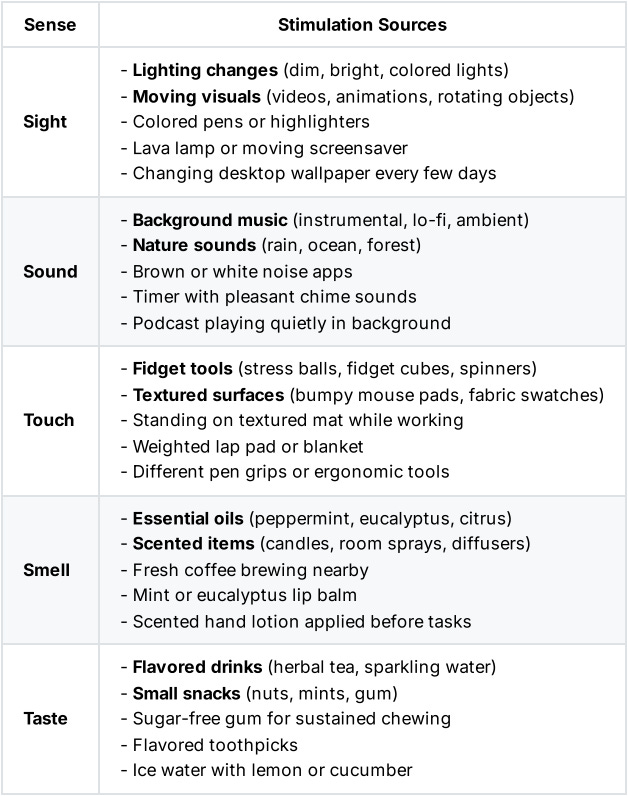

🔲 Choose one of the example stimulation sources from the list below. These are just examples…there’s plenty more sources you can find or use:

🔲 Set a timer for 5 minutes to do the task with this single source safely integrated. Notice if the task feels slightly more manageable or if you can stay focused longer.

🔂Repeat this until you have 2-4 sources that are mildly helpful, then move on to ‘Step 3’

Step 3: Layer Sources

🔲 Set a new 5 minute timer, and layer 2-3 sources then do the task again. Notice if the task feels even more manageable or if you stayed focused longer.

Step 4: Create Task-Specific Combinations

🔲 Write down what combination of sources worked on a sticky note: this is your first completed Menu!

🔲 Put that Menu in a somewhat intrusive place where you do that task (e.g. hanging slightly off the edge of your computer desk, or on your keyboard)

Step 5: Refine and Rotate

🔲 Swap sources if they stop working (you will get bored eventually)

🔲 Keep your top 2-3 Menus attached to each other, and cycle through them!

And that’s it: Congrats!!

Note: This can take time to refine, but once you have a few Stim Menus for a given task, I’ve noticed I can just cycle through them without having to refine or make new ones.

Here’s a quick copy/paste of this method:

STIM MENU BUILDER

□ Pick 1 boring task you do regularly

□ Test 1 'stimulation source' for 5 min

□ Find 3-5 mildly helpful sources, then layer them together

□ Write winning combinations on sticky note (i.e. Your New Menu!)

□ Place Menu near the task location

□ Create/Refine Menus until you have a 2-3 for a task

□ Rotate Menus when they get staleOk…that's a wrap on understanding why your brain seeks stimulation!

The key insight here: you're ADHD brain is not addicted to chaos, it is strategically hunting for stimulation so it can detect what you need and if you’re heading in the right direction. Once you understand this, you can recognize the “chaos” for what it is, and then deliberately layer in stimulation to get in the zone.

Thank you for reading this far!

If this issue helped clarify your relationship with "chaos," please consider sharing it or restacking some quotes from it.

To all my subscribers, two things:

1) you rock, thank you so much for being here, and

2) I’ll be sending you a free downloadable PDF next week with another way to dial-in your focus.And, if you haven’t subscribed yet, do so before that free PDF is sent out:

Until next week, and as always, sending good vibes your way.

Cheers,

Michael

P.S. I’ve decided not to mention what I’m going to write for the following week, mostly because I end up writing something completely different than I intended to and end up going back to the previous issue to edit what I said I would write…ADHD is so weird…

You rock for sharing things like this in a kind and compassionate way.

Having sources and building stim menus makes total sense! I hope I use the correct words here: I have tasks, including household maintenance and cleaning, that I simply cannot do without certain sources in place. When everything is in place, I can complete tasks in much less time than when I don’t. Similar to what you described about writing therapy notes. For example, by itself, one sink of dishes would take me an hour to load into the dishwasher and I couldn’t finish without the necessary sources. But with the right sources, gloves and music and a timer for 15 minutes (my ideal stim menu for this task) it takes me five minutes.

I feel like some of the issues of my ADHD are masked by my autism - and vice versa, probably another reason I didn't realise that I was AuDHD for such a long time. I don't think I could ever listen to any background noise to initiate focus for instance, noise is a huge sensory issue for me. I need a quiet, distraction free space (easier said than done right!) and even then it still takes a long time to get in the zone.... But once I'm in, I can stay there. The problem with that, obviously, is the need to commit to that initial start up. Some good ideas there that might help that process, and interesting information about the reasons behind it, thanks.